By: Anna Hughes

The Cybercrip

The summer before I started my practice-based PhD a mysterious sickness struck me. Determined not to let it get in my way, I carried on. I presumed that these symptoms would resolve themselves somehow, but they never did. Instead, my illness developed. Eventually, I realised I could not carry on as before any longer. I needed to adapt. I needed a different way of working because making large sculptures was becoming too much of a strain on my changing body. In research, well-considered methods are essential. A method is how something is done, and these choices need a particular logic. Sickness involuntarily became a part of my methodology because it helped shape why I do things in a certain way. My body not only affected my way of doing things but also nurtured my ability to respond creatively to this body’s influence. As a way of continuing to make art and my research, I turned to digital media. Digital space operates differently from analogue space because I can do so much with minimal bodily movements. Embodiment is now a fundamental part of my methodology, yet my methods centre around me “using” my body less. Despite its apparent disembodied ephemerality, cyberspace is a vital form of mobilisation, creativity, work, and socialisation particularly for sick and disabled people. With my research, I emphasise not only the creative utilisation of cyberspace within disabled and chronically ill communities but also the importance of these voices in developing cyberspace as an embodied encounter. We have learned to adapt with and for our bodies, becoming adept at a genuinely hybrid, digitally augmented body, and the methods we develop can be learned from. The cybercrip.

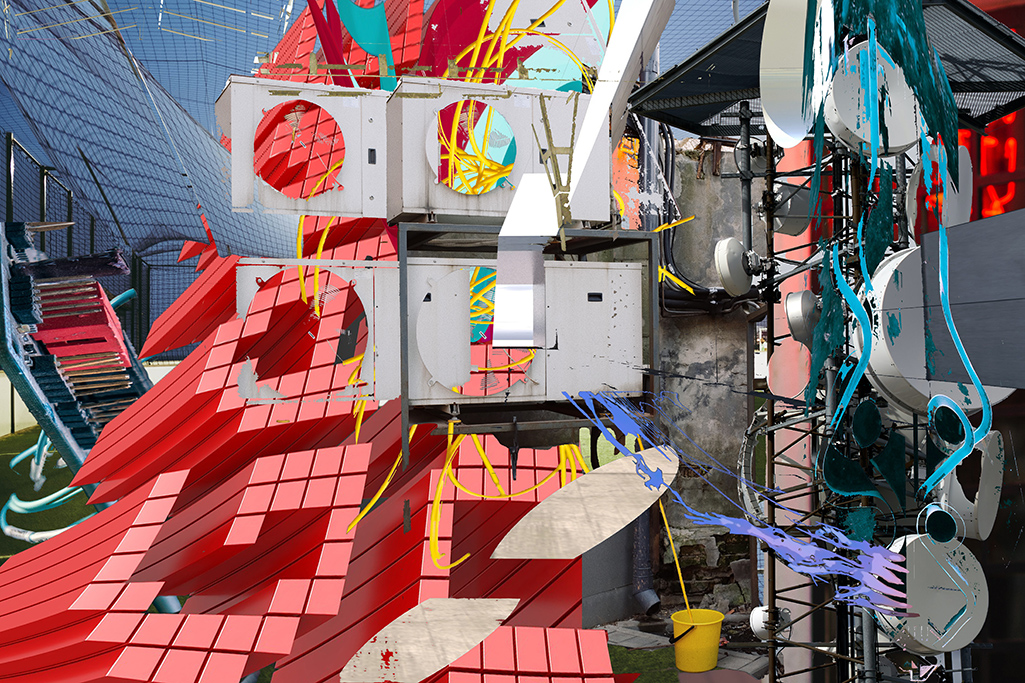

Using the computer graphics software program Blender I learn to make things differently. Sculpture no longer feels accessible to me. I need to limit how much I move my own hands to make artwork. Digital making is a way in which I can open up space, and continue with my research project. My body is no longer a passive object in the decisions I make concerning methods. I soon realised that this form of making offers me more than a substitute for working with my hands: I can use this software to add more space and open up different understandings of the things I make. In Blender, I make myself a digital hand. I endeavour to recreate the creases and folds of my own hands creating an object that looks realistic. Crafting these details myself, I spend time with this new creation. I know this hand. I perfect the skin material that covers this severed hand, careful to accentuate the depth of the skin surface by including the “dermis” layer which appears red and splotchy on the hand. With this hand, I can reach out in cyberspace. The digital hand is not my avatar, it is a digital prosthesis that allows me to interact in digital media. The uncanniness of this digital hand does something to me, making it more than a representational object. The uncanny is what pulls me into this bodily appendage, and not its ability to become a “real” hand. I feel through it, as I use it to touch and interact with other materials in my digital artworks. With this digital hand, I learn how embodiment manifests in cyberspace, and nurture my relation to embodiment in general as a sick person. I learn both the science of my body and the effects bodies have on one another. Cyberspace does not need to be a space of disembodiment.

Online Resistance

My sick body extends into cyberspace. I turn this movement into a creative output. Cyberspace has been designed by and for capitalist greed. Capitalism profiteers from disability while it uses us to benchmark the limits of normality. Disabled people, therefore, need to hack these capitalist systems to gain any benefit from using their digital facilities. This disruption is a practice in itself. Legacy Russell coined the term Glitch Feminism.1 Russell argues that the glitch can be utilised as a means to disrupt. Reclaiming the error as something agential is useful for my body that is being consumed by unexpected sensations. The error is a creative endeavour. Preset algorithms dictate interactions in cyberspace; therefore, the error creates difference and produces much-needed alternative pathways. In a system without error, we see much repetition, even if this system grows in a feedback loop. The error is a new way forward. The error is innovation despite whether it is a positive or negative interruption. Without an interruption (error, anomaly, breakthrough, or shift in a system, even a system of thought), momentum is contained to a predetermined path, meaning invention is only possible through deviation. Illness diverts us in the course of a “healthy” path. Instead of thinking of this change in direction as something to be corrected, we need to leave room within our systems for change; without the assumption that things should and will achieve expected results (a healthy/”normal” body) and function in expected ways. Creativity, then, would be built into and cultivated within a system. The sick body is a creative body, and with it, we find different paths forward and different methods of being and being with others. This creativity stems from the body while it creates symptoms, mutations, disease and more. It also creates the need for a change in method. Ultimately, disruption is critical to combat the marginalisation capitalism shapes.

The collective Laboria Cuboniks introduces such tactics in their manifesto Xenofeminism: A Politics for Alienation.2 This manifesto expresses optimism for technology to disrupt the patriarchal, capitalist practice of marginalisation. The manifesto strongly rejects “essentialist naturalism.”3 Essentialism is a harmful prospect for those who differ; it posits a fixed expectation despite its unattainability. In this instance, nature is thought of as possessing an undisputed sanctity. Naturalism itself is not the problem. The problem is the proposition that things possess inherent qualities. In this way, there is a quintessential human from which all others deviate, creating a hierarchy of perfection. In contrast, crip theory does not form itself around a central figure (the perfect human) from which any difference creates deviation. Crip theory decentralises what it is to be human, allowing for deviation to create a multiplicit picture of humanity (as well as non-humans). Crip theory puts the power of collective difference into practice, allowing for the integration of variation through finding common goals, desires, and needs. Most importantly, crip communities are formed through subjective decisions to include oneself in this group, as opposed to being made a part of a group through exclusion, which the essentialist human dictates.

For disabled people, essentialism is a frightening, othering prospect. All this fixity completely bypasses the reality that “nature” is composed of change. Medical care can be thought of as either the proof that bodies are malleable, autonomously changing and liable to being changed, while, on the other hand, medicalisation has long reflected a desire to correct and indeed eradicate disabled people. The medical model of disability has been widely criticised for its problematization of disability. The medical model of disability focuses on the impact of an “impairment” or illness on the individual and emphasises the need to medically intervene with the intent to cure disability. The medical model frames disability as a negative thing to be corrected, therefore emphasising the “deviance” of the disabled person. This model fails to see disability as a viable difference, where disability can cultivate thriving culture, joy, skills, knowledge, and creativity. Importantly, the medical model focuses on the individual at the expense of acknowledging how one’s society is designed in such a way as to disadvantage disabled people, which reflects society’s disregard or prejudice towards disability.

To counteract the medical model, the social model of disability has become the preferred ethos for the majority of disability rights campaigners today.4 The social model of disability argues that society actively disables a person and not that their body disables them. The need for accessible buildings and the eradication of stigma is crucial for this movement. This model does not seem perfect to me, however. If society is the one barrier that causes disability then it also posits that disability can be eradicated with social changes. I am disabled; all the bodily difference, knowledge and experience have made it a crucial part of who I am. I do not know who I am, or if I will be me anymore without disability. Furthermore, there are certainly social changes that would make things easier and less symptomatic for me, but having a genetic disorder means that my body creates symptoms and functions in a way that disables me. Social attitudes also impact the politics around medical care, which greatly affects my disability. The social model is important to consider because social design hugely affects disabled lives, but there needs to be more to it. Disability is a “complex embodiment” one that combines the social and the embodied, as Tobin Seibers would argue.5 Medical intervention can be vital, while society causes its scarcity, neglect, abuse, and malpractice. Disability need not be cured, and Alison Kafer argues that the assumption of cures in the future assumes a better world is one without disability, while it undermines the need to plan for disability in the future.6 Disability is neither positive nor negative; it is a reality that creates different ways of being. Disability is a way of being as a body, as well as with other bodies.

Medical intervention does not need to be framed as a correction, or a cure for disability. Medicine should be the creation of technology that relieves difficulties and suffering. Medicine is not always necessary for all disabled people, but it should be treated no differently from innovation in assistive devices/aids or accessibility features: something that is available and prioritised when needed or wanted. Medicine and assistive technology are both creative responses to the body. In the text, ‘Crip Technoscience Manifesto’, Aimi Hamraie and Kelly Fritsch argue that

“Disabled people design our own tools and environments, whether by using experiential knowledge to adapt tools for daily use or by engaging in professional design practices. Crip technoscience conjures long histories of daily adaption and tinkering with built environments.”7

Technology gives agency if we use it to deviate beyond the “norm” as opposed to preserving normality through medical corrections. Bodily “hacking” through medical intervention is given as an example of technological disruption in Cuboniks’ cyberfeminist manifesto.8 Cuboniks explains that the black market distribution of hormonal pharmaceuticals resists the gatekeeping of gender affirmative care. The internet provides us with medical knowledge as well as access to structures of exchange. Cuboniks acknowledges the dangers of unregulated medical markets but argues that these underground practices model a better way forward, calling for a “free and open source medicine” platform.9 Open source software holds the user-focused advantage of being free, but it also provides the user with the source code, enabling them to modify the program. This open-source model brings into question the withholding of vital care that pharmaceutical profiteering creates.

The project Get Well Soon by Tega Brain and Sam Lavigne serves as an online archive of well-wishes from GoFundMe campaigns for medical care. They state that “it is an archive that should not exist.”10 As Cuboniks identifies, people are assembling and taking healthcare into their own hands online. The well wishes archived may offer hope for society’s capacity to care and help others, yet this archive only exists because of a lack of state-provided medical care;11 a result of inconsistencies in society’s capacity to care for all. This charitable crowd-sourced system is vital for particular individuals but without the fair contribution and distribution of these medical provisions.

All the well-meaning messages in this archive do show that care can be easily distributed online, as Laboria Cubonix points towards open-source-style medical care. The sporadic distribution of the GoFundMe campaigns means crowd-sourcing individual care is not the most ethical way forward because it inevitably selects and excludes people for varying reasons including bigotry. Cuboniks calls for a form of “health communism” exemplified by open-source medical care and considers fair distribution, unlike a crowd-sourced charitable model. This argument goes beyond the socialism of our current NHS system in the UK (putting aside the point that the NHS is being systematically decimated through austerity measures, driving the appeal of private treatment). The NHS’s main principle of being available to all is important, but we could enhance this system beyond simply funding it properly: the open-source model is not only about universal accessibility (free to use), but it also provides an infrastructure where individuals can contribute knowledge and agency to a collective endeavour. In this way, patient care becomes both medical and social at the same time. Agency and subjective knowledge become crucial in this new way forward that includes new systematic technologies and a collective responsibility to care and share with others in a community.

We can take from these well-wishes the prospect that care can be accumulated and distributed online but we must remember that medical distribution systems need to move on from individualised empathy.

Crip Cyberspace

Cyberspace is equipped for the user-based self-inclusion that characterises crip theory. Crip theory focuses on self-assembly and fluid definitions, forming a coalition of crips drawn to the other through a commonality in being disabled. Robert McReur uses queer theory in his introduction to crip theory. He explains, “able-bodiedness, even more than heterosexuality, still largely masquerades as a nonidentity, as the natural order of things.”12 For McRuer, disability and queer theory originate from what he calls “compulsory able-bodiedness” and “compulsory heterosexuality.”13 Both disability and homosexuality arise as other to the “norm.” Crip theory identifies disability through commonality. This commonality does not need to be exact symptoms; it could be a commonality in being othered or marginalised as a body. The act of reclamation involved in using what was once a slur (queer or crip) gives the group agency; disability is not to be seen as positive or negative but a legitimate reality in need of acknowledgement. Although instigated through marginalisation, a crip community still forms itself by affirmation of those who are drawn together when previously classification was given to them without consent.

Touching Bodies at a Distance

Cyberspace enables me. It assists me, or moreover, it facilitates my movements in a more accessible format for me. Digitally, I can create whole worlds, be they expressed visually or conceptually. My expressions of this embodiment create a world. However, in cyberspace, this world is open. Creating different worlds is an invitation; a form of reaching out to others so they can encounter something new. The mobility of cyberspace is built into its functionality and material composition. With this in mind, other practitioners in cyberspace can be learnt from. How do others utilise the “affective” potential of cyberspace?

An online phenomenon I have been drawn to is ASMR (Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response). ASMR videos feature sources of sensory stimulation, isolating and intensifying particular sounds (triggers), visual and material properties, often being manipulated in some way by hands or other objects, as well as sometimes just using whispered speech. The desired effect is a tingling at the back of one’s head, or simply, relaxation.

A YouTube video created by ASMRMagic has garnered an astonishing ninety-two million views to date (2024).14 In this hypnotic footage, the creator delicately interacts with an array of objects, evoking sensory responses in viewers. I find myself entranced as manicured fingers trace the surface of a glitter-covered mannequin head, the sound of the glitter crackling beneath each gentle stroke. My body absorbs this sound, and I feel this crackle at the back of my head. I feel a resonance with this sound as it transforms and amplifies itself on my own skin. A side effect of a medication I take called Midodrine (for Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome) is a tingle at the back of my head. When I feel this sensation I know the medication is taking effect. This medication helps pump blood around my body. A nurse was surprised when I announced that I liked the tingling the first time I tried the drug. This tingling reminds me that my body is working to be me. Similarly, ASMR instigates this tingling sensation. The phenomena that I encounter outside my body, reverberate with me. These sensations collapse traditional notions of proximity because I am no longer so separate from the screen. Paradoxically, something outside myself has produced such strong sensations in my body. Illness produces a similar outcome in that it forces me to feel my body. Relief from these symptoms does not need to be a neutralisation of the body, but it can be something that therapeutically produces its own effects, like warmth, tingling, or euphoria. Illness is creative in this way and is perhaps why I seek sensation from all that I consume.

Digital software has given me the means to create things in an accessible medium for me. Online media platforms give a means to share and interact with things created. Digital/digitised art is formatted in such a way as to be compatible with this form of presentation and dissemination. Before becoming sick, I did not fully understand the importance of this formatting: with digital media I can reach things now rendered out of reach. I can reach out to others and find ways to resonate with them. This is particularly liberating for those unable to reach out in “physical” ways. Beyond individual efforts to reach out in cyberspace, digital media gives the means to collect and mobilise embodied knowledge that is often under-represented, particularly in medical settings. I have participated, and learnt from others with my medical conditions in dedicated forums. Without such knowledge, I would never have solved the mystery of my illness when doctors could not diagnose it. Digital media allows us to find each other through embodied commonalities. Art-making is an attempt to reach out to others and find these resonances, and digitisation broadens this reach. As with the example of ASMR, digital art requires another body to feel something for it to reach its potential. Artist and theorist Simon O’Sullivan explores this potential of art to instigate “affects” in those who encounter it.

“Affects can be described as extra-discursive and extra-textual. Affects are moments of intensity, a reaction in/on the body at the level of matter.”15

In making digital art, I draw from things that resonate with me as a body in the hope that another body might respond to it. It is not the outcome of this reaction that is meaningful for me as the artist, but the thought of this potential. Like when I have participated in online forums, I have resonated with others despite such a seemingly indirect mode of connection: one body putting their knowledge “out there” for others. The potential that art, or a shared phenomenon holds excites me.

ASMR is a good example of what I can do with the specificity of cyberspace. Using cyberspace as a disabled person is more than an alternative method in response to a loss of access to the “original” method. With digital media, I can make things without straining my body, and I can use it to reach others, whether I consume the material of others or contribute and interact socially with an online community. Illness has instigated my use of digital media as an art-making method, but it also inhabits the work I create. Illness has taught me that my body is present in everything I do, only before, I did not notice it: my body was quiet in the background. I know now that making artwork is an embodied move; a move that is both practical and knowledge-based. Digital media has given me the means to both directly express what it is to be this body, as well as how to produce as a body. Illness and embodiment have become a framework for my art-making methodology. The methods I have adapted with come with their own methodology and techniques designed and instigated through/for digital media. There is a reciprocal relationship between developing methods in response to the body’s needs and the media that facilitates these methods. A feedback loop that creates difference because the body autonomously diverts my study away from repetition. I must adapt and change with this volatile body. Cyberspace gives me particular abilities, while my body contributes to how and what I make using these new abilities.

The Cybercrip

The cybercrip acknowledges that embodiment is key to disrupting capitalist systems online. My theory of the cybercrip is not necessarily aimed at sick and disabled people; we already know that the embodied subject cannot be superseded by “rationality” and that cyberspace can be a useful tool when “physical” access is not possible/viable. The cybercrip is to affirm the vital knowledge of cyberspace that disability/sickness/non-normativity nurtures; we are bodies who have learnt to find alternative methods, ready to adapt, divert and disrupt dominant platforms in cyberspace, bringing forth embodied practices using this seemingly ephemeral augmentation.

BIO

Born 1990, UK. Anna is a visual artist, writer and researcher based in London. She has recently completed an art practice-based PhD titled Sickness in Cyberspace: Sensual Encounters in Digital Media Towards a Radically Embodied Future, supervised by Melanie Jackson and Tai Shani at the Royal College of Art, London. Anna also completed an MA in Sculpture at the RCA in 2014. Her work has been exhibited with institutions across the UK and abroad including Southwark Park Gallery, Beaconsfield Gallery, QUAD (Derby), Outpost (Norwich), Hackney Picture House, Flattime House and Art Copenhagen.

REFERENCES

- Legacy Russell, Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto (London New York: Verso, 2020). np. ↩︎

- Laboria Cuboniks, ‘Laboria Cuboniks | Xenofeminism’, accessed 16 September 2019, https://www.laboriacuboniks.net/. ↩︎

- Ibid. np. ↩︎

- For an example of these campaigners see Disability Rights UK, ‘Social Model of Disability: Language | Disability Rights UK’, accessed 1 February 2023, https://www.disabilityrightsuk.org/social-model-disability-language. ↩︎

- Tobin Siebers, Disability Theory, Corporealities (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2008), 25. ↩︎

- Alison Kafer, Feminist, Queer, Crip (Indiana University Press, 2013), 1–2. ↩︎

- Aimi Hamraie and Kelly Fritsch, ‘Crip Technoscience Manifesto’, Catalyst: Feminism, Theory, Technoscience 5, no. 1 (1 April 2019): 5, https://doi.org/10.28968/cftt.v5i1.29607. ↩︎

- Cuboniks, ‘Laboria Cuboniks | Xenofeminism’. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- ‘Get Well Soon!’, accessed 13 October 2020, http://getwellsoon.labr.io/. ↩︎

- The project, Get Well Soon! was made in the US, so the lack of medical care is amplified compared to the UK. Still, in the UK, the NHS is running insufficiently due to austerity which forces individuals to seek private care and fundraise. ↩︎

- Robert McRuer, Crip Theory: Cultural Signs of Queerness and Disability, Cultural Front (New York: New York University Press, 2006), 1.

↩︎ - Ibid, 2. ↩︎

- ASMRMagic ‘ASMR 50+ Triggers over 3 Hours (NO TALKING) Ear Cleaning, Massage, Tapping, Peeling, Umbrella & MORE – YouTube’, (YouTube video, 3:16:49, 2018) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oXp0hTkXiks&t=2187s.

↩︎ - Simon O’Sullivan, ‘THE AESTHETICS OF AFFECT: Thinking Art beyond Representation’, Angelaki 6, no. 3 (December 2001): 125–35, https://doi.org/10.1080/09697250120087987. ↩︎