SYSTEMS/HACKING

Editors’ Intro: Issue 2 (2024)

Our systems are broken. Let’s hack them to pieces and sell them off for parts.

Though a halcyon glaze, hacking has been immortalised as agential resistance against oppressive power structures: David versus Goliath; Greta versus the climate; Cady against the Plastics. Yet a critical survey of contemporary hacker networks finds them entrenched in the existing regimes of power such that archetypal binaries of this nature fall flat. As anthropologist of hackers Gabrielle Coleman rightly observes, “One prevalent way of framing the hacker has been by casting him as the male hero-technologist who conquers the electronic frontier”.1 Think about the hackers of our age: the so-called good ones like Eddie Snowden or the incarcerated Assange, or the real bad ones: the increasingly AI-generated Zuckerbaby, or Elon the worthless billionaire. What do they have in common? Besides their obvious identity signifiers, there is an undeniable frontier mindset engrained in each. Whether it be the infinite of outer space or the faux-walls of the metaverse, they share the belief that people, place, and everything in between is a data point to be detected, extracted, entrapped and liquified.

Yet in the months since we conceived of this issue, wrote the open call, and put it out into the world, it’s become increasingly clear, if it wasn’t obvious already, that our systems are broken. Could we reclaim hacking as a way to dismantle hegemonic ills to reconstitute a system that runs autonomously, fueled by something other than extractivist practices of devastation?

Since its inception as an illicit remote breaking into computer systems, hacking has undergone a myriad of metamorphoses, fragmenting into a multiplicity of computing practices, or practices that pirouette across the surfaces of computational frameworks and into the terrain of flowing blood and blooming flowers. Its objective, on the other hand, has remained steadfast: hacking uses the tools forged by the system to disrupt, deprive, disassemble that very same system. In this sense, hacking is a way to cultivate knowledges anew, to deviate from the rigidity of systems closed to external input and internal aberration.

Could we situate hacking as an alternative knowledge, a fraying edge on the broad expanse of epistemology? Donna Haraway claims that knowledge “does not pretend to disengagement”;2 it always comes from somewhere, not out of nowhere. Karen Barad also insists knowledge is not preexistent, rather, materialised—if we may interject—from and through its system.3 Tim Jordan’s genealogy of hacking demonstrates hacking as “the engagement with redetermining information technologies” and hackers’ “drive to redetermination, to always being in a determinative relationship with information technologies while also always using that situation to change determinations, is a way of expressing and exploiting the rationality of information technology.”4 Substitute Jordan’s ‘information technologies’ with ‘systems’, and you get McKenzie Wark’s hacking: “To hack is to differ…The slogan of the hacker class is not the workers of the world united, but the workings of the world untied.”5

After all, what are hackers without systems? And without hackers, systems will not reveal themselves for what they are. SYSTEMS/HACKING is an inquiry into this enmeshment, a first step to help the infrastructure break apart, before an inevitable rebuild.

DiSCo Journal’s second issue features 10 ‘hacks’ that exemplify hacking as a digital and/or analogue mode of intervention or deviation from a system. These hacks are diverse in subjects, methodologies and (re)presentations to reconsider hacking as knowledge, and at times, nonknowledge existing off of sheer irony.

The most prolific hacks cut across embedded processes to guilefully affect systems in ways that resist detection, appearing as a glitch or rupture unattributable to intentional disruption. As explored in Tanvi Kanchan’s experimental essay on performing digital illegibility, ways of glitching to subvert, to “poison the system” transcends the barrier between the physical and the digital to queer the reality it imposes on us. In a related vein, Sam Moore’s video essay and accompanying text on body horror, glitches in the Matrix, and monsters poetically meld together the idea of slippages and the trans body as a way to break binaries, gender, code, and otherwise.

To obfuscate one’s digital presence is another way to hack the platforms that track our every click and comment. Charlotte Lengersdorf challenges writing’s key function to convey meaning in written language through her essay and videos of asemic writing, or a visual form of meaning-less writing, as an abrupt break from legibility. erynn young gets into the weeds of self-censorship practices on TikTok through “@lgosp3@k” strategies, thinking through their implications for subverting and bypassing the social media platform’s content moderation practices. Peter Conlin asks “Have you been on petittube.com, and if not, why not?” He advocates for the French video platform’s search for “the least interesting videos on the internet” as a hack against the hyper-targeted recommendation system of YouTube.

Yet hacks as a method of subversion have often been coopted by neoliberalism’s efficiency fetish such that the very system it seeks to dismantle enfolds it into its flesh. Cutting through the neoliberal entrails of hustle culture and self-help, Max Oginz writes on the circular temporality of online manifestation, its relation to sleeping and dreaming, and its evolution in the digital age to critique Capital’s mindfulness cult. Relatedly, Rebecca Miller experiments with ways to reclaim sleep via sound therapy in the form of inner tree recordings, capturing its effects on her sleep, and by extension, her creative output.

And sometimes the best way to hack the system is to create your own system from what you already know or possess. Centering sickness and crip theory as methodology, Anna Hughes takes us through her journey as a disabled researcher looking at how ASMR or re-creations of her physical body as digital in Blender enable a digital embodiment that surpasses the physical body. projektado collective presents an interactive media piece exploring the radicality of friendship as an anticapitalist, relational process of learning, living and organising. Entering into the choose-your-own-adventure dialogue with a mysterious, all-knowing figure, the reader can engage in an esoteric conversation that gradually unveils the reader-figure relationship as simultaneously contingent, precarious and precious. Finally, we are welcomed into the cosmology of the Shona people, a tribal community of modern-day Zimbabwe. Chipo Mapondera’s virtual reality (VR) world takes you to the silent sleeping pools of the Chinhoyi Caves, a sacred place IRL defamed by colonial programming. Rather than traditional trappings of gaming culture with its ubiquitous violence, “power-ups” and horseplay, in this VR you can find solace, through sound, space and communal ceremony, offering a glimpse into what technological systems can be.

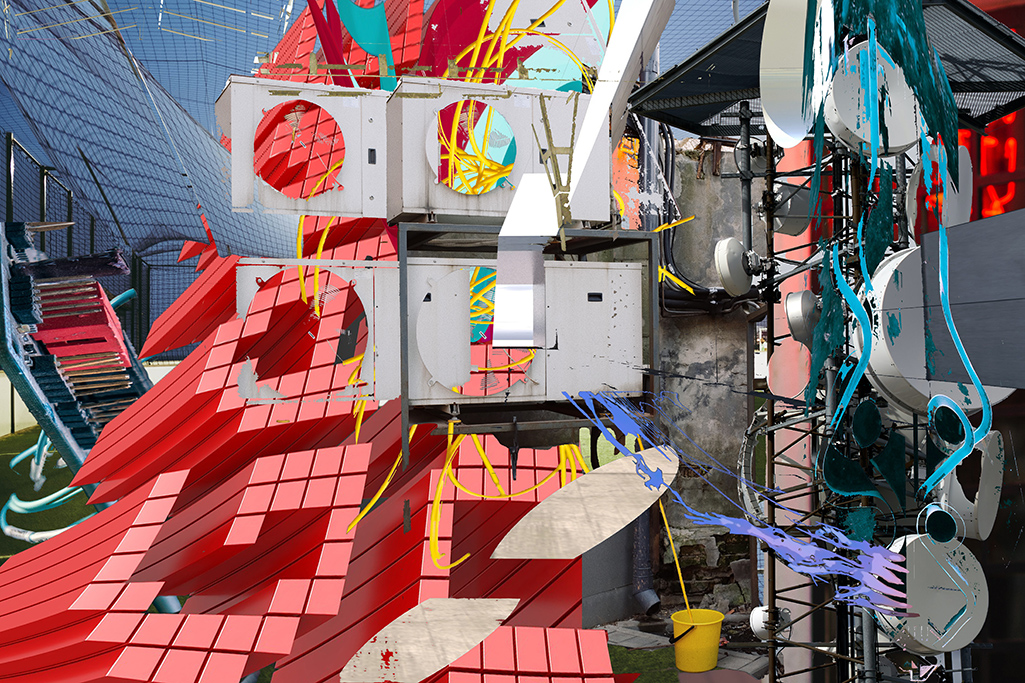

We are also privileged to present our first artist residency with net artist-cum-urban farmer Heath Bunting. Often affiliated with the ‘90s net.art movement, Bunting worked in the early medium of the internet, parodying the avant-garde movements of the twentieth century. His net art projects toyed with the protocols of the street and the early net, exploring topics on border crossing, identity and data, social protocols, hacktivism and the politics of public space. For the residency, Bunting led the Blockchain vs Foodchain workshop for which he and the workshop’s participants discovered creative radical strategies around Bitcoin mining/investment and growing vegetables to prepare for the then-looming energy crisis instigated by the Ukraine-Russia war. In addition, he has also contributed to the issue homepage’s quirky graphic icons connected by the hashtag next to the articles’ hyperlinks. The icon images are Bunting’s visual interpretations of the articles’ contents, and their function as interventional conduits mimics the tactic of online spam pop-ups, which is, in a way, a sinister mode of hacking a user’s data. The hashtag colonises the homepage like a virus or an ambiguous symbol of nonknowledge, which both forefronts the articles and provides an idiosyncratic levity to the (sorta) seriousness of the issue’s theme.

Finally, but certainly not least, a huge kudos to our fabulous web designer Andrea Elena Febres Medina for all her work and time in to the redesign, and to our wonderful editorial committee* who helped us actualise SYSTEMS/HACKING.

It’s easy to fall into hopelessness and despair at the state of current affairs, as our institutions, from education to government, continually betray our voices. Cynicism abounds as small acts of resistance, tiny hacks resembling papercuts, are dismissed for their impermanence and insignificance. What does blocking celebrities who have stayed silent in the face of genocide really do, one might ask? One small act may do next to nothing, but the collectivised hacks that inch towards change may add up. What does commenting, unfollowing, or blocking do? Could it confuse the algorithms, could it affect their bottom line? The cables of cause and effect are not so simple as to allow one to claim these hacks, both big and small, both digital and physical, to lead to definitive, systemic change. Yet a million papercuts will bleed you dry. And this system, broken as it is, deserves to wither.

🪓Let the hacking commence 🪓

<3

Sandy Di Yu

Sarah Hwang

Tanvi Kanchan

Craig Ryder

[DiSCo Journal Managing Editors]

*Sarah Molyneaux (Birkbeck)

REFERENCES

- See Gabrielle Coleman and Peter Jandrić, “Postdigital Anthropology: Hacks, Hackers and the Human Condition”, Postdigital Science and Education Vol 1 (2019): 525-550. ↩︎

- Donna Haraway, Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: the Reinvention of Nature (London: Free Association Books, 1991), 196. ↩︎

- Karen Barad, Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning (London: Duke University Press, 2007), 361. ↩︎

- Tim Jordan, “A genealogy of hacking”, Convergence 23, no 5 (2017): 541. ↩︎

- McKenzie Wark, A Hacker Manifesto (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 2004), [003] and [006]. ↩︎