By: Liz Blum

Digital Oz

Keywords: art; digital; technology; dystopia; landscape

The life of an image in the digital network exists forever, untethered to history, people or place. It persists into the future in its digital afterlife, piling up against the rest of technology’s digital universe, its presence a construct made of code and data. We respond to them by scanning our devices as pinch-to-zoom viewers in the hope that we can uncover something beyond the visual surface.

This ambiguity of experiencing the image through the virtual functions of our devices reflect back a false reality, surfaces a psychological awkwardness in the subject. This uneasiness is the ideological self, expressed between physical flatness and projected infinity, a portal into the digital world that highjacks our insatiable appetite for attention, validation and comfort.

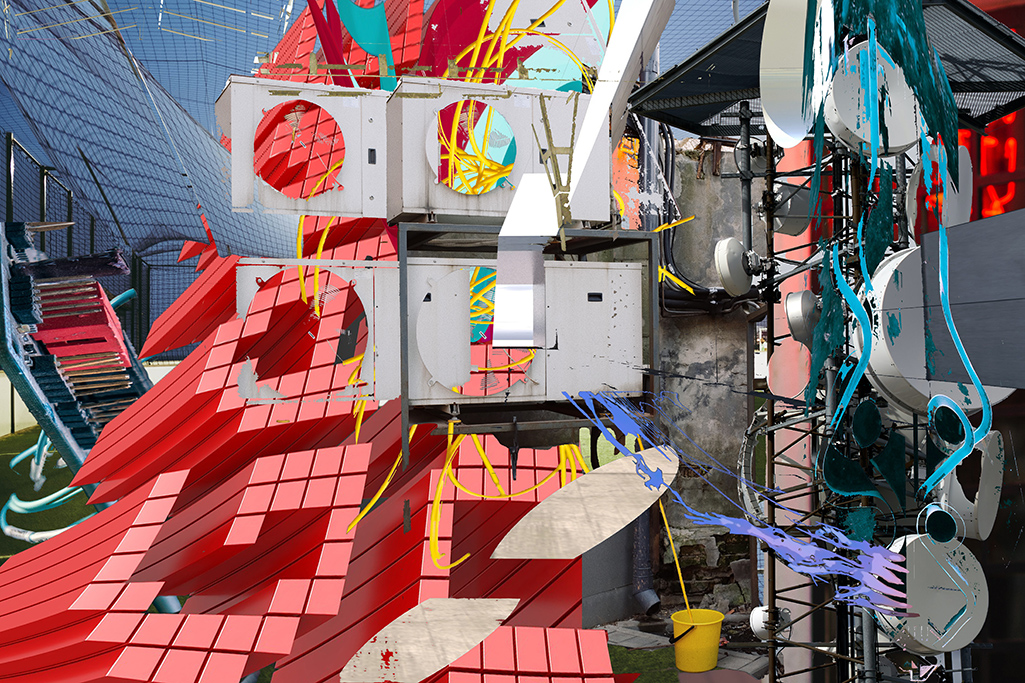

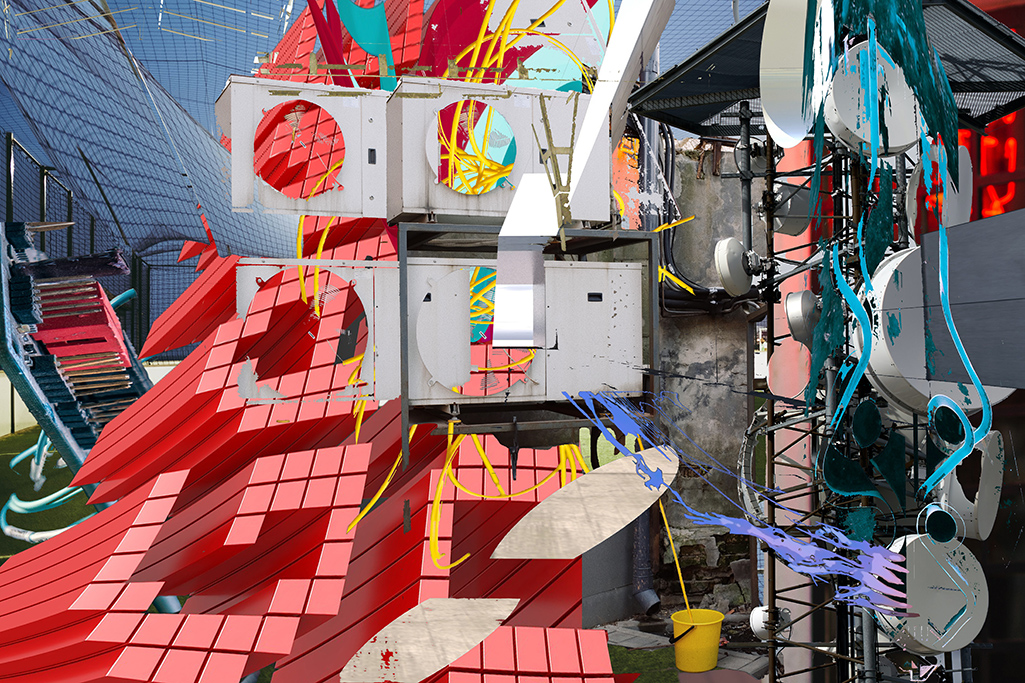

The work featured here visualises this psychological awkwardness, to find out what lies at the periphery of the digital realm, and to come up with an idea of what could be imagined there. To picture this unseen dimension within the network of our technological world as untapped metaphysical spaces, it aims to decipher the world behind the screen, uncovering events occurring in the digital shadows. Employing the aesthetics of the digital world, through hallucinatory environments, it moves from voyeuristic horror and wonder to mercurial voids.

My work interprets the technologies we use, the internet, computational processes, technology infrastructures, and the digital realm at large as a kind of ‘nature’, symbolic landscapes, complex structures of digital ‘hives’ and networks that reflect the use of digital technology as subconscious digital torment.

I also see these topics as comparisons to cultural and political systems, a tangled web of missteps beyond the undo, products that address contemporary worlds as digitised dysphoric landscapes that dissolve realistic forms into abstracted structures. The look of real objects contrasts with invented forms, suggesting that we create worlds teetering on collapse or else mutating into unlivable topographies.

The work imagines these environments as alternative visions beyond the familiar digitised chatter, constructed glitch, or coded variables, visualising instead computational processes as events that pollute our information highways; a virtual ‘toxication’ of the network that lurks in dark corners of the web. In Afterglow and Oz, division of space animates fictional screen interfaces to reveal digital noise, digital applications and hardware, presenting malleable and fluid scrap as collapsed and destroyed bubblegum spaces, tripping with the idea of technology’s efficient and invisible aesthetic.

These digital ‘inner-lands’, the innards of our devices, compress time and space into technological breakdowns, luring our digital selves into temporal quagmires at warp speed and unnaturally hyping our thought processes. This compression of space-time is at the basis of connectivity, reinforcing FOMO and necessitating our consumer desires, illustrating the potential outcomes of a capitalist world powered by speedy fibre optic cables and algorithms.

In The Condition of Postmodernity: An Enquiry into the Origins of Cultural Change, David Harvey outlines how space-time-compression produces prevalence of capital, relying on communication and digital media to initiate and capture time to power innovation and grow our modern society. Referencing this, ClickBait reveals bold and directional forms plugging into each other. The space condenses to a shallow depth while (hyper)links bounce off surfaces in an imagined pinball scenario. In a similar vein, digital space reaches a tipping point in Happy Valley, the essence of magnetism compressing looping connections into a balancing act. Here, deep space produces a slow churn of cyber traffic that maybe links up, maybe not, but ultimately presents seductive trails of lost connections, to be repeated over and over again.

Cultural activist and philosopher Bernard Stiegler, writing on technology’s overreach and control on society, believes that digital networks are counter to our natural cognitive process, suggesting that it creates “the net blues” and that anything transformative that new technology was supposed to bring has instead created “stunned paralysis”. Overload hints at this toxic scenario, a collapsed structure of motherboards and hard drives, with imagined Ubers rides couriering our online behaviours towards the iCloud chained to the inner workings of the digital sphere, serving up access at any time.

We tap away online, unaware that with every click we contribute to the mechanics of a much larger network, industrial infrastructures, that supply salvaged minerals, rare earths and toxic metals, materials that go into the manufacturing of our devices, contributing to the destruction of our planet. It doesn’t stop there. Supply networks, satellite systems and underwater cable networks deliver digital outputs, but when the machinery becomes outdated, it piles up in galaxies far, far away as space junk or pollutes our marine ecosystem.

In her article A Rare and Toxic Age – A journey into the complex and parallel mythologies of modern technology and rare earths, Ingrid Burrington writes, “Synthesizing that star stuff into iPhones (and hard drives, lasers, fiber optic cable,Teslas, and a vast array of other networked or software-defined electronic devices) requires a vastly complex global supply chain and carries significant environmental costs”.

In SpaceJunk, network detritus sails through space, floating and crashing into other junk that piles up over time. Waste orbits the Earth, the result of our spent digital usage, a skyscape where illuminated hashtags replace the stars at night.

GameOver signals an end point as a crumbling text monument, an ode to time spent in the video game sphere. The network “netting” is not really there to save or protect us or to deliver another life but to hold us in place between crash and burn or advancing to next level.

Denaissance, a play on the word Renaissance, is an attempt to solidify digital time within the context of failing greatness. The image denies the cultural rebirth promised by technology. Stylistically different to the other works, it stages classical architecture with a plinth acting as a foil to the discarded iPhone in the bucket. Warped chiaroscuro illuminates nothing except a discarded security camera and the empty casts of digital shadows.

Purgatory and Soup set themselves apart as not obviously portraying technology’s materiality. Fictional and scenic in nature, each landscape is an allegory, a requiem to time leached from us, never to be recovered. The two portals suggest neither a beginning nor an end, but a point where our digital being is temporally stuck in some hidden vortex or latent space.

Technology can be predictable, but the human spirit less so. We act as magpies, picking up information here and there, distracted each time by some shining new titbit of information that comes our way through the networks and systems of pixels and code. If indeed the devil is in the details, then the ambiguity of what we see through the “mirrored” virtuality of our devices reflects back a tangled web of neurotic connections.

[end]

BIO

Liz Blum is a multi-disciplinary artist and collaborative researcher based in Boston. Currently working between the US and UK, her approach is driven by a process of collecting data, research, and information to interpret as visual and digital imagery or performative events. Her work investigates the environmental concerns within the digital sphere and technology. She received her MFA from SUNY at Albany, New York, exhibits her work both locally and internationally and has contributed writing and work to, House Letters, The Scaffold, Folium Publishing, London, Murze Magazine, Extinction Rebellion, London, ToolBook, Soho, NYC, On Contemplation, ELSE The Journal of International Art, Literature, Theory and Creative Media Transart Institute, Photographic Powers, Aalto University/Aalto ARTS Books, Helsinki, Finland. Her work can be viewed at lizcooperblum [dot] com

REFERENCES

Abbinnett, Ross, The Thought of Bernard Stiegler Capitalism, Technology and the Politics of Spirit. Abingdon: Routledge, 2018.

Burrington, Ingrid. “A Rare and Toxic Age.” Increment. February 18, 2018. https://increment.com/energy-environment/a-rare-and-toxic-age/

Harvey, David, The Condition of Postmodernity : An Enquiry into the Origins of Cultural Change. Cambridge, Mass: Blackwell, 1990.